ARTICLES

The Data Person as Project Manager

This post accompanies my talk at the 2018 Women in Statistics & Data Science conference (full slide deck). The header photo was taken while enjoying some snacks and beverages on a hill in Tuscany on a spring afternoon; it represents the serenity I want all of us to feel about these project management tasks. #goals

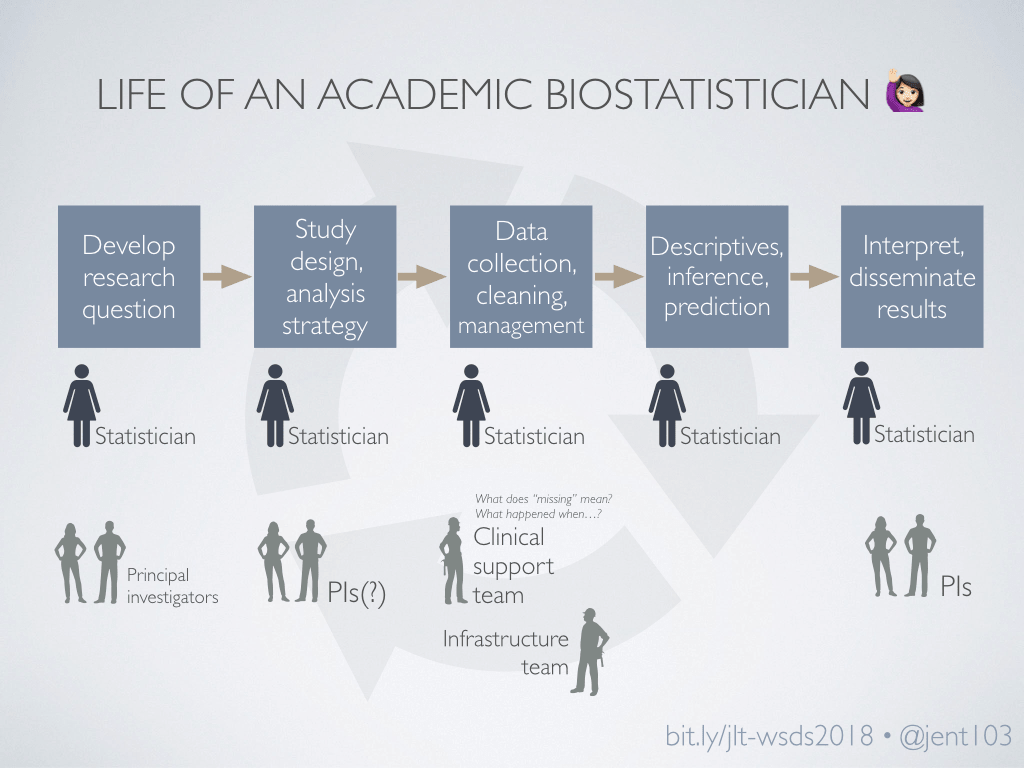

I’m currently the primary biostatistician working with a group of over ten clinical researchers. This means lots of projects - and lots of people with sometimes conflicting timelines and priorities. We have a fantastic team, parts of which are involved at different points in our project timelines - but the stats team is often deeply involved at every step.

This is often true for corporate data science as well: there are business stakeholders involved at some points, domain experts or infrastructure teams at other points, but the data scientist is there for the entire timeline.

In my experience, since we’re involved at every step, we often manage these steps, at least in part: juggling multiple stakeholders’ timelines, making decisions based on information from data entry or infrastructure teams, creating more efficient processes, and following up on tasks or decisions needed for us to move forward. In short…

…if there is no formal project manager, often WE become a project manager.

This has advantages! We build a deeper knowledge of the data, the project, and the domain, and stronger relationships with the infrastructure or data entry team as well as the stakeholders. This leads to more rigorous analysis, more relevant interpretation of results, and more effective communication of the clinical or business impact. Plus many of us genuinely enjoy this work! I love the sense of collaboration and ownership I feel when I’m this deeply involved in a project.

As any project manager will tell you, though, project management (PM) is a lot of work. And if time doing PM work takes away from technical work or development, it might actually hold us back professionally.1 So it’s in our interest to manage our projects efficiently!

Our stats team have developed some successful PM strategies for our context. Your mileage may vary; I hope you’ll take these ideas and tweak them to work in your specific context.

Communication

When I first started working with our research group, I would get individual, uncoordinated requests from each investigator. As an inexperienced new employee who wanted to make everyone happy, this was a difficult situation! We now have a weekly meeting of primary stakeholders - in our case, the biostats team and all the principal investigators. This is incredibly helpful for getting our team on the same page, coordinating our priorities and timelines. It also allows team members to learn from one another: our research fellows learn how to work with the statistical team by watching how we interact with the more senior PIs, and the biostatisticians develop a better understanding of the clinical background and impact of each project.

We also keep a list of priorities available to everyone in the group, so all the stakeholders know what projects are on my list and have a sense of when I might get to them. This also facilitates conversations about changing priorities or timelines. (We keep it simple and do this via a Slack channel that I update weekly.)

Focus

What are your group’s goals? Revenue, grants, patient care - you can have several, of course, but delineating them “out loud” gives you criteria for which projects to take on and which should take a backseat. Our group is full of fantastic ideas, but we’ve absolutely had times where we spent time on a project we all thought was interesting, but that never quite got done (or got done… eventually), because it turns out those projects weren’t really getting us to our goals at that moment. It happens to the best of us, and we can learn from those experiences.

Once you’ve determined a project is worth taking on, and you’ve defined its initial goals, we all need to watch out for scope creep. Scope creep might sound like “as long as you’re ___, can you look at these three other things too?” Or “Wait, what happens if we do it THIS way?!” These can be great ideas worth incorporating! But sometimes they just derail us from our mission. Creating a project plan, then documenting the inevitable changes to your plan, is incredibly helpful for setting your intention; for making sure everyone understands the goals and methods of the project; and for outlining the steps that will help your team get to your goal.2

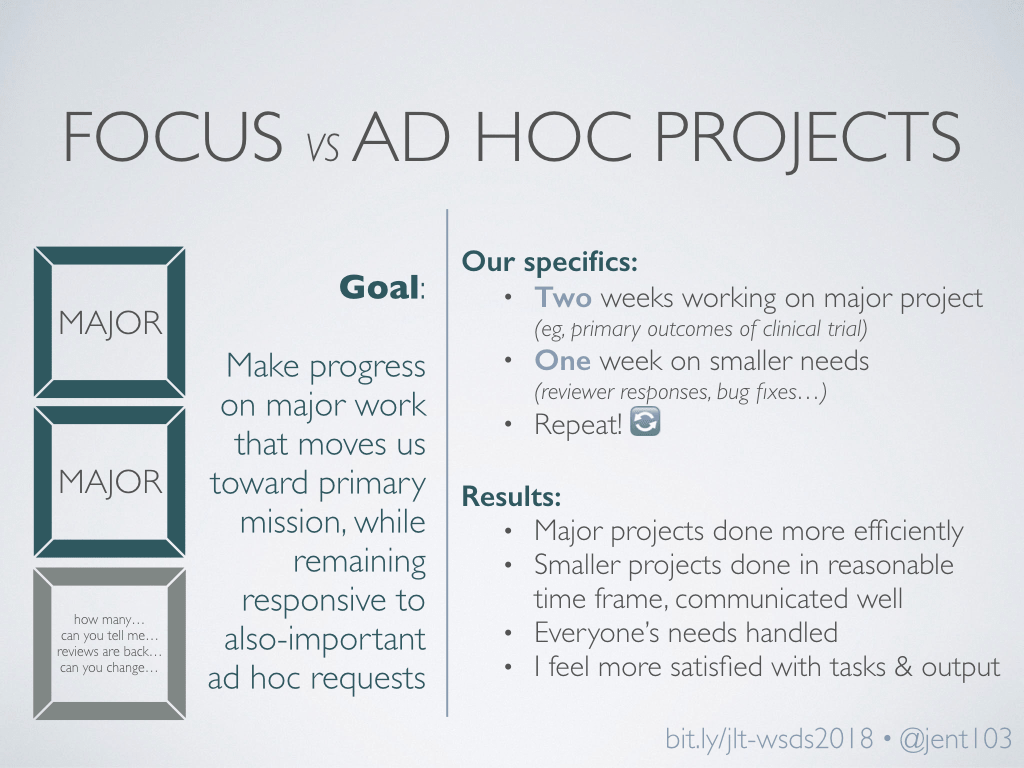

Of course, having the best plan in the world doesn’t help if you can’t actually execute it. There are many weeks when I come into work thinking I know exactly what I’ll be working on, and end the week wondering just exactly where it went. (🙋 if you feel me.) Getting “distracted” by smaller, one-off requests can be not only frustrating for the analyst, but keep the team from focusing on our primary goals.

We’ve instituted a system inspired by software development strategies: I spend two weeks working on “major” projects that require lots of focus and move us toward our group goals, and the next week on important but smaller projects that can be stacked and done in batches. These might look like those “hey, can you tell me how many people…” requests, or journal revisions, or tweaking visualizations.

We’ve been using this system for about six months now; it has allowed us to push a major project through to publication in a reasonable time frame (with much happier biostatisticians), while still allowing the daily business of clinical research to take place. In short, I’m a big fan.

As some audience members at WSDS rightly pointed out, this is difficult to do if you’re in a situation where you have multiple stakeholders who aren’t coordinating with each other. (A typical academic statistician often has her time split between several unrelated projects. How do you execute this “focus vs ad hoc” approach for a project that only funds 17% of your effort, with work required in bursts, and is with a collaborator who doesn’t communicate with any of your other collaborators?) That’s a tough question I haven’t solved. If anyone has great ideas, I’ll happily link to them here!

Process

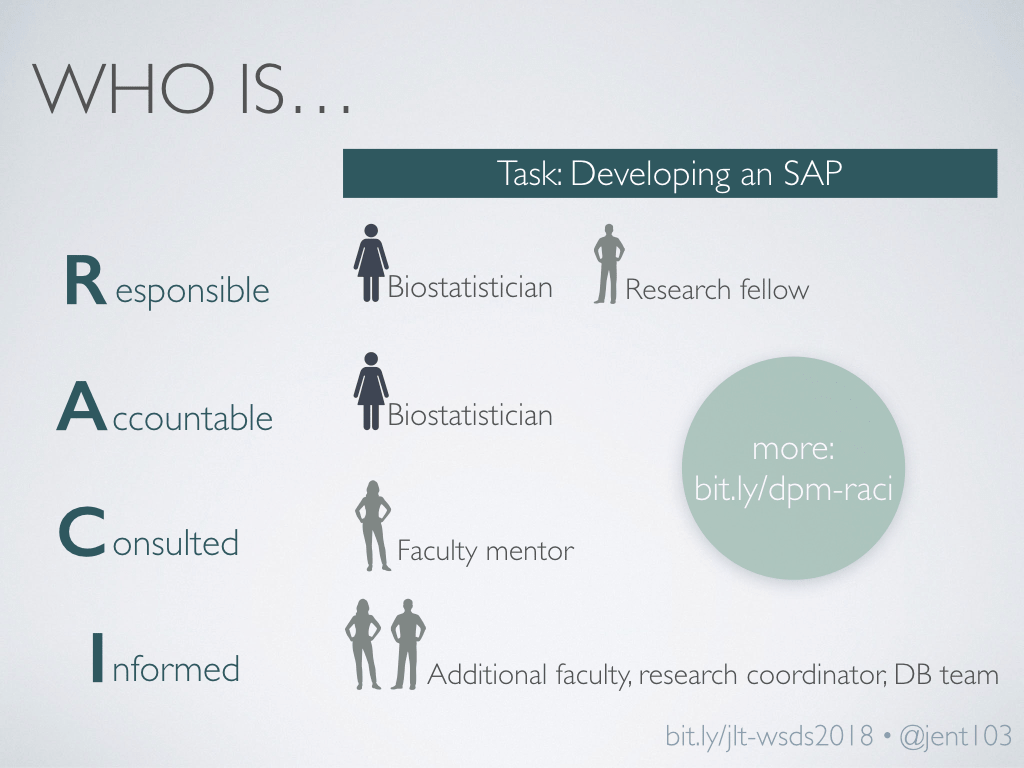

In your typical project, who is involved in making decisions about analysis plans or communication strategies? Hopefully we, the data people, are, along with the primary stakeholders. There might be additional stakeholders - mentors or supervisors. Maybe we have a database team or other infrastructure folks who help decide on data storage. Maybe we have a statistical colleague with expertise in a particular area… maybe we have a C-suite or a department chair we need to make happy… (You see where I’m going with this.) Eventually, there are many people in the metaphorical room, and we think every decision needs to be run by all of them. This creates confusion, not consensus.

Enter the RACI matrix, which helps streamline decision-making processes. For any given task, define who is responsible for executing the task; who is ultimately accountable for the task; who is consulted on decisions related to the task; and who is simply informed about those decisions.

Knowing the core team responsible for a specific task means we know who to include in each decision. This means we don’t miss getting input from key team members, and don’t spend time waiting on consensus from the people who aren’t directly involved. We haven’t gone through this formal process with the whole team, but even using it as an informal framework for individual projects has been immensely helpful.

We’ve also recently started using a project request form for new statistical projects, which helps us learn:

- The reason/goal for the project

- Who is accountable for the project, + additional team members who will help steer it (ie, the RACI matrix!)

- Logistical information (always deadlines!; in our context, that also includes IRB permissions, any manuscript drafts or table shells that are already written, and funding/data sources)

This information helps us prioritize, streamline, and keep an eye out for any logistical hurdles we need to overcome before starting analysis or planning.

We’re also working on onboarding documents for new team members, with information like how and when to contact the biostats team; where our documents and data are stored; and what we expect both of our investigators and of ourselves. We hope that collecting all this information in one spot will be useful for our new clinical and statistical team members, and help emphasize that we’re all on the same team with the same goals. TBD!

Systemic Considerations

It’s important to understand what is valued by your organization and the career path that you’re on - and to know what you value! If you’re in an academic tenure track position, for example, most likely no one on your promotion committee is asking you how efficiently your collaborators’ first author papers were written, and thus it doesn’t make sense to spend a lot of your time on these tasks - but they may be highly valued in a different position or organization. Understanding what will move you forward and what you enjoy is key to meeting your own professional goals as well as your team’s.

If you’re a manager or a supervisor, please be aware of how much “glue work” your employees are doing! A lot of us in data-related fields are collaborative by nature, aiming to be helpful and fix inefficiencies. That is valuable to our teams, but if we’re spending “too much” time on tasks (PM or otherwise) that won’t be considered by those doing the promoting or hiring, it will hurt us long-term. New employees aren’t always in the best position to know what “too much” looks like in their organization, and supervisors can provide resources and valuable calibration.

Recognition & Thanks!

- The VUMC Strategy & Innovation Office has some great training workshops including some on project management, which is where I learned some of these techniques. If you’re at a large organization, I’d highly recommend looking into similar options.

- My supervisor Rameela Chandrasekhar has been a hugely supportive teammate and collaborator in developing and supporting these practices!

- Many thanks to Jesse Mostipak and Sharla Gelfand who helped make sure this talk/post would apply to all data folks, not just those in academic environments.

More Resources

- Trey Causey on why data scientists make good product managers (product management != project management, but some similar points)

- Tanya Reilly on “Being Glue”

- Roger Peng on balancing resources (time, technology…) and analysts managing the flow of information

Tanya Reilly has a fantastic talk on doing this “glue work” as a software engineer; a lot of it is applicable to us as data scientists as well. Thanks to Sharla Gelfand for sharing this talk!↩

In our academic research context, we’ve successfully used our statistical analysis plan to handle this. We recently had a major clinical trial published; particularly in that scenario, the SAP is a big deal, and we registered ours publicly so that it’s clear that we didn’t do any manipulation of our outcomes after we knew the treatment assignments. One added advantage of that formal registration: Whenever one of us got an idea for additional analysis while we were working on the primary manuscript, we were able to collectively say “That’s a great idea. We’d have to update the SAP, and it would be after we broke the blind. Is it important enough for that?” And in this case, the answer was always no. :) Keeping that project focused using the SAP meant we were able to publish our work efficiently, without being derailed by interesting but secondary side questions. The most important ideas will come back up in later discussion, and we’ll develop a thoughtful plan for them then.↩